Reconnecting nature and agriculture: emancipatory practices in agroecology

Carolina Yacamán Ochoa, UAM

2024

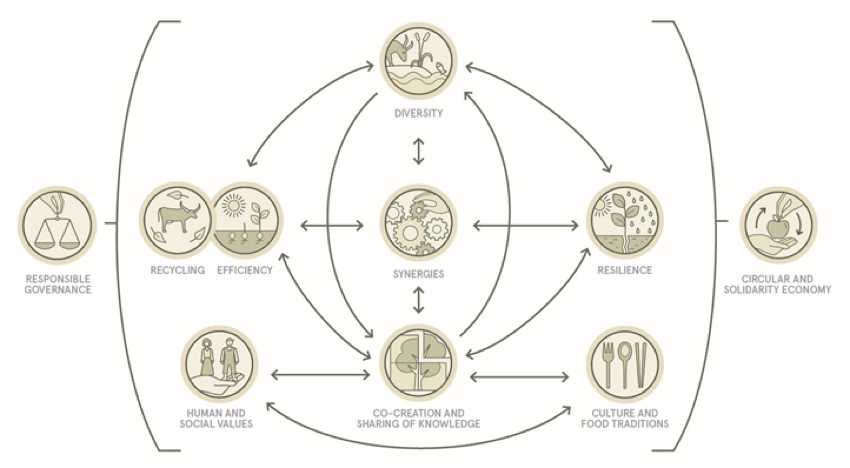

Agroecology, which emerged in the mid-1990s, originated as a form of resistance to the transformations in local food systems brought about by the Green Revolution, monoculture practices, industrialization, colonial dynamics, and the growing corporate control over seeds and food production that created the actual ecological breakdown. In recent years, it has evolved by adopting a holistic framework (based on 10 elements), not only promoting significant practices to mitigate one of the major environmental impacts of industrialized food systems on climate change—by reducing dependence on fossil fuels, and synthetic inputs (efficiency) in favor of nutrient recycling and organic matter utilization (synergies) and promoting closed energy loops (circular economy) —but it also strives to restore food sovereignty to enhance community resilience.

FAO’s 10 elements of agroecology framework to guide transformative change pathways towards sustainable food and agricultural systems (FAO, 2018)

In contrast to the dominant corporate food regimes, agroecology reinforces non-capitalistic, peasant, and indigenous livelihoods, while safeguarding traditional and biocultural knowledge. This is done mainly by redistributing productive assets like seeds and land among local communities (natural resource governance) and reshaping food practices (soil health, animal health, enhanced biodiversity) through commons-based approaches essential for the reproduction of life. It promotes democratic control over the means of production, while promoting harmony with nature (human and social values)

In the following paragraphs, we will discuss emancipatory practices aimed at reconnecting nature with agriculture and integrating diverse traditional worldviews. These practices enrich the agroecological approach by framing it within a biocentric perspective, linking it to the commons, and emphasizing the preservation of cultural diversity, the genetic richness of seeds, ancestral knowledge, and respect for ecosystems.

Minga – a cultural and ancestral Andean practice- deeply rooted in a collective effort for community benefit and preserving indigenous worldviews is a tradition that is closely aligned with agroecological principles. Tthe focus extends beyond sustainable farming methods to fortifying community bonds through social organization (participation)— and mutual support values that are intrinsic to the Minka concept. When community members come together to do collective agricultural tasks or construct communal projects, they engage in a form of agroecological practice by fostering a self-supporting community structure. This commoning practice embeds local food systems and strengthens community cohesion.

Agroecology, a practice grounded in principles of biodiversity preservation, finds an ally in seed bank movements like Navdanya in India, the Seed Guardians Network in Quito, and La Troje in Spain. These agroecological networks preserve native seeds, which is fundamental for maintaining biological and cultural diversity in farming systems. Seed banks directly address impacts created by the industrial agricultural model, such as the loss of genetic diversity and dependence on patented GMO seeds. By emphasizing peasant-led practices for seed conservation and non-profit exchanges, these movements not only secure food sovereignty but also empower local communities, enhancing their self-reliance and democratizing food production in the face of corporate food system pressures.

The Rural Schools of Agroecology (ECAS) in the Andes Tulueños and the Universidad Autónoma Indígena Intercultural (UAIIN) in Colombia exemplify a critical approach of co-creation and sharing different types of knowledge (diálogo de saberes). These institutions illustrate the importance of valuing and sharing different dialogs and practices throughout the life cycle, involving different actors like the family, spiritual authority, community, cultural and political authorities. Their approach leverages ancestral knowledge to manage holistically the food systems and to improve agrobiodiversity, including the production of medicinal, ornamental, and food plants. This diversity is essential to reinforce the spiritual and cultural connections that communities have maintained with nature across generations, emphasizing the deep ties between cultural diets and food traditions.

Specifically, the UAIIN aims to recognize the collective memory, wisdom, and traditional practices acquired from the roots of indigenous cosmovision, allowing a deeper understanding of Mother Earth. Additionally, they view education within the context of the eco-social crisis as a means to strengthen worldviews, local economies, and food sovereignty. To achieve this, they utilize horizontal pedagogical processes that share local, technical, and academic knowledge, particularly through indigenous peasant farmer exchanges, fostering the creation of community bonds and promoting good living (Buen Vivir). It is also essential for building political movements necessary to achieve deep transformations. This institution, along with many others engaged in biocultural critical thinking, are essential for constructing a political narrative rooted in frameworks that shape alternative collective rationalities within their respective territories.

These examples highlight the significant contributions of agroecological movements that have a collective political project dedicated to defending indigenous and peasant agriculture, their traditional practices, and common goods—elements that are crucial for transitioning towards a degrowth world. These examples become even more critical when considering the negative externalities—such as resource depletion, air, land, and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity loss—resulting from the growing dependence on petrochemical-intensive agriculture. In this context promoting food as a common versus a commodity becomes essential. Finally, at the heart of the socio-ecological crisis, agroecology gains strength with its political, scientific, and social dimensions to facilitate pathways of transformative change towards territorially-based, resilient, and culturally appropriate food systems.

Further readings and resources

FAO (2018). The 10 elements of agroecology: guiding the transition to sustainable food and agricultural systems. http://www.fao.org/3/i9037en/i9037en.pdf

Gliessman, S. (2018). Defining Agroecology, Agroecology and Sustainable

Rosset, P., Barbosa, L. P., Val, V., & McCune, N. (2021). Pensamiento Latinoamericano Agroecológico: the emergence of a critical Latin American agroecology?. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 45(1), 42-64.

Shiva, V. (2016). The dharma of food. In Religion and Sustainable Agriculture, ed. T. Le Vasseur, P. Parajuli, and N. Wirzba, 125–133, vi-ix. Kentucky: Univ. Press of

Toledo, V. (2022). Agroecology and spirituality: reflections about an unrecognized link, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, DOI: 10.1080/21683565.2022.2027842